Module 03: Deterministic Agent Flow with LangGraph

Chains respond in sequence. Graphs respond with purpose.

This module marks the transition from demo-quality agents to production-ready systems using LangGraph. It explains why linear chains fail in production and how graph-based architectures solve the problems of explicit control flow, state management, and error handling. You’ll learn to build agents with deterministic workflows using nodes and edges, implement conditional routing for decision-based execution paths, add checkpointing for pause/resume capability, and create retry logic with exponential backoff. The module culminates in building a multi-stage research agent that demonstrates all these production patterns in action.

LangGraph, Graph-based Architecture, State Management, Deterministic Control Flow, Conditional Routing, Checkpointing, Error Recovery, Retry Logic, Production Agents, Workflow Orchestration, Observable Execution, StateGraph

What You’ll Learn

This module is where things get real. Up until now, you’ve been building agents with simple chains—linear execution, implicit state, hope for the best. That works for demos. It doesn’t work for production.

Here’s what actually separates toy agents from production systems: explicit control flow. You need to know exactly what your agent is doing, be able to pause and resume it, handle errors gracefully, and route based on actual decisions—not just hope the LLM figures it out.

The Core Skills

Graph-based architecture - Why workflows need to be flowcharts, not pipelines. Chains execute sequentially with no branching. Graphs let you make decisions, loop back on errors, and handle the messy reality of production.

Explicit state management - Everything your agent knows lives in one place that you can inspect, save, and resume from. No more hidden state buried in conversation history.

Deterministic control flow - Define exactly how your agent moves through its workflow using nodes (what it does) and edges (when it does it). Conditional routing means “if error, retry” not “if error, ¯_(ツ)_/¯”

Checkpointing and retries - Save state after each step so you can resume from failures. Implement retry logic with exponential backoff. This is what makes agents production-ready.

Observable execution - See exactly what your agent is doing at each step. Debug based on facts, not guesses.

By the end, you’ll build a multi-stage research agent that can pause, resume, retry on errors, and show you exactly what it’s doing at each step.

Module Structure

- Time: 5-6 hours with exercises

- Prerequisites: Modules 1-2 complete, basic grasp of state machines (if-then-else counts)

The module splits roughly into:

- 30% Understanding why chains fail

- 30% LangGraph fundamentals (nodes, edges, state)

- 25% Advanced patterns (checkpointing, retries, routing)

- 15% Building the research agent

The Exercise

This module features one comprehensive exercise that builds a research agent with deterministic flow:

- Step 1: Define State (20 min). Create a typed state schema for the research workflow.

- Step 2: Define Tools (30 min). Implement web search, content extraction, and summarization tools.

- Step 3: Create Nodes (45 min). Build nodes for research, analysis, synthesis, and review phases.

- Step 4: Build Graph (30 min). Wire nodes together with conditional routing and checkpointing.

- Step 5: Execute with Checkpointing (25 min). Run the agent with pause/resume capability.

- Extension Challenges (60 min). Add retry logic, parallel execution, and visualization.

Why This Actually Matters

The patterns in this module prevent the most expensive production failures.

Deterministic control flow means you can reason about your agent. When something breaks at 3 AM, you need to know exactly what path the agent took and why. Graphs give you that visibility. Chains don’t.

State management enables debugging, testing, and compliance. You can inspect the exact state that led to a failure. You can write tests that verify state transitions. You can audit what your agent knew at any point.

Checkpointing turns catastrophic failures into resumable tasks. Without it, a timeout on step 47 of 50 means starting over. With it, you resume from step 47. At scale, this saves thousands of dollars in wasted compute.

Retry logic handles the reality of external dependencies. APIs fail. Rate limits hit. Networks timeout. Proper retry patterns with backoff prevent these transient failures from becoming user-facing errors.

Companies that adopt LangGraph report 40-60% reduction in agent-related incidents. The explicit control flow makes problems visible before they become production fires.

The Problem with Chains

In Module 2, you built agents using tool-calling loops. They work. But they have problems that only show up when you try to deploy them.

# Traditional chain approach

result = (

prompt_template

| llm # or "claude-sonnet-4"

| output_parser

| tool_executor

| llm # or "claude-sonnet-4"

| output_parser

)What’s wrong with this?

Linear execution - No conditional branching. Every step runs in order, always. Can’t skip steps or change the path based on what happened.

Implicit state - State is hidden in conversation history. Want to know if the search succeeded? Good luck finding it in message arrays.

Non-deterministic - Same input can take different paths depending on what the LLM decides. Debugging is a nightmare.

Hard to debug - Execution is opaque. Something failed on step 7? Hope you added logging everywhere.

Difficult to resume - No checkpointing. If it crashes on step 8 of 10, you start over from step 1.

What production actually needs:

- Explicit state you can inspect

- Conditional routing based on decisions and errors

- Ability to pause, resume, and retry

- Observable execution paths

- Deterministic behavior (same state → same path)

This is where LangGraph comes in. It’s built specifically for this.

Why Graphs Beat Chains

Workflows Are Flowcharts, Not Pipelines

If you look at the Linear Pipeline in the below diagram, the mental model is simple: input goes in, steps execute in order, output comes out. There are no choices to make and no way back. This works when every step is predictable and success is assumed.

But when you look at the Workflow Graph, the shape immediately changes. On a whiteboard, you don’t draw a straight line. You draw boxes and arrows with questions in between:

- Do I need a tool?

- Is the answer good enough?

- Should I retry with more context?

Those questions become decision nodes, and the arrows coming back to the LLM become loops. Tool calls feed results back into the same reasoning step. Low-confidence answers trigger retries instead of silent failure. That structure is a graph, not a chain.

The key difference isn’t visual—it’s architectural: Pipelines execute steps. Workflows make decisions under uncertainty. Once your agent can branch, retry, or re-evaluate, you’re no longer building a pipeline. You’re building a flowchart—and your architecture needs to reflect that.

What LangGraph Actually Gives You

Explicit State Management

Chain approach:

# State is hidden in conversation history

messages = [

{"role": "user", "content": "Find sales data"},

{"role": "assistant", "content": "Searching..."},

# State is implicit - hard to track what happened

]LangGraph approach:

# State is explicit and typed

class AgentState(TypedDict):

messages: List[Message]

task: str

search_results: Optional[List[Dict]]

retry_count: int

status: Literal["searching", "processing", "complete", "error"]Why this matters:

- You can inspect state at any point

- State transitions are observable

- Easy to persist and resume

Conditional Routing

Chain approach:

# All steps execute in order, always

chain = search | process | format | respondLangGraph approach:

# Route based on state and decisions

def route_next_step(state: AgentState) -> str:

if state["status"] == "error" and state["retry_count"] < 3:

return "retry"

elif state["search_results"]:

return "process_results"

else:

return "ask_for_clarification"Why this matters:

- Different paths for different scenarios

- Handle errors gracefully

- Avoid unnecessary work

Cycles and Loops

Chain limitation:

# Cannot loop back to previous steps

# Must restart entire chainLangGraph capability:

# Can loop for retry, refinement, or iteration

graph.add_edge("validate", "process") # Success path

graph.add_edge("validate", "refine") # Needs improvement

graph.add_edge("refine", "validate") # Loop backWhy this matters:

- Self-correction loops

- Iterative refinement

- Retry mechanisms

Checkpointing

Chain approach:

# If it fails, start over

# No intermediate state savedLangGraph approach:

# Save state at each step

checkpointer = MemorySaver()

graph = graph.compile(checkpointer=checkpointer)

# Resume from last checkpoint

result = graph.invoke(state, config={"thread_id": "123"})Why this matters:

- Fault tolerance

- Long-running workflows

- Human-in-the-loop at any step

Observability

Chain approach:

# Black box execution

result = chain.invoke(input)

# What happened inside? 🤷LangGraph approach:

# Every state transition is logged

for step in graph.stream(state):

print(f"Node: {step['node']}")

print(f"State: {step['state']}")

# Full visibility into executionWhy this matters:

- Debugging

- Monitoring

- Audit trails

When to Use Graphs vs Chains

| Scenario | Use Chain | Use Graph |

|---|---|---|

| Simple linear workflow | ✅ | ❌ |

| Single LLM call | ✅ | ❌ |

| No branching logic | ✅ | ❌ |

| Needs conditional routing | ❌ | ✅ |

| Error handling & retries | ❌ | ✅ |

| Long-running workflows | ❌ | ✅ |

| Needs checkpointing | ❌ | ✅ |

| Multi-step decision making | ❌ | ✅ |

| Production agents | ❌ | ✅ |

Rule of thumb: If your agent has more than 3 steps or any conditional logic, use a graph.

LangGraph Core Concepts

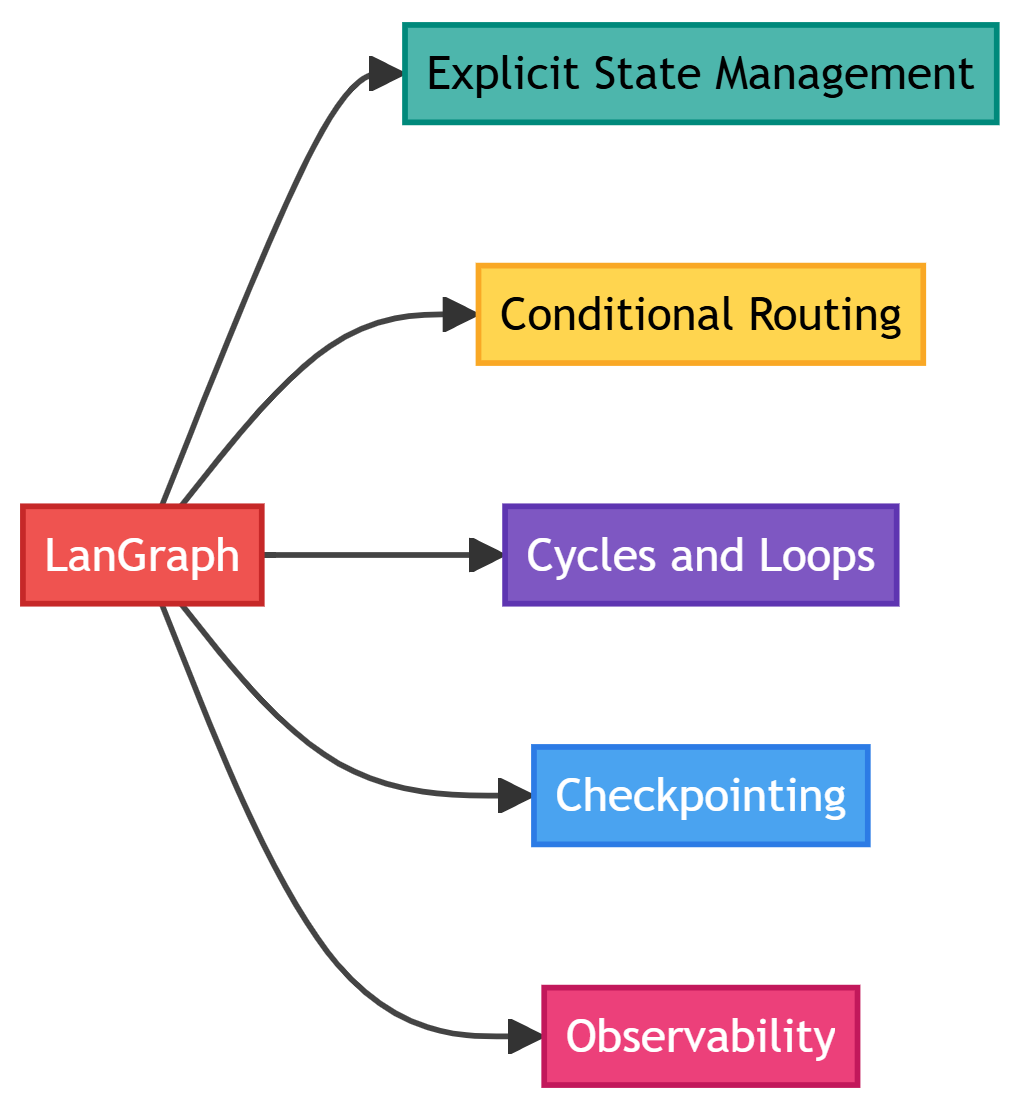

The following diagrams illustrates the core components of LangGraph and how they interact with each other.

Let’s go deep in each component one by one.

Part 1: State, Reducers, Nodes and Edges

State (The Agent’s Working Memory / Single Source of Truth)

State is where everything your agent knows lives. Not in variables, not in message history—in one structured place you can inspect and modify.

The following two Python examples illustrates how you go about building state step by step.

Step 1: Start Simple

from typing import TypedDict

class MinimalState(TypedDict):

"""The absolute minimum: just messages."""

messages: list

# This works, but you'll want moreStep 2: Add What You Need to Track

from typing import TypedDict, Annotated, Sequence

from langchain_core.messages import BaseMessage

from langgraph.graph import add_messages

class AgentState(TypedDict):

"""Production-ready state with everything you need."""

# Conversation - special handling for appending

messages: Annotated[Sequence[BaseMessage], add_messages]

# What are we doing?

task: str

current_step: str # "planning", "executing", "validating"

# Retry logic

attempts: int

max_attempts: int

# Results

final_answer: str | None

# Status tracking

status: str # "running", "complete", "error"

error_message: str | NoneWhat each field does:

- messages: Conversation history. The

add_messagesannotation means new messages get appended, not replaced. - task: The original user request. Never changes, always available for context.

- current_step: Where we are in the workflow. Useful for debugging and routing.

- attempts/max_attempts: Retry tracking. Prevent infinite loops.

- final_answer: The output we’ll return. Separate from intermediate work.

- status/error_message: Execution state. Makes error handling explicit.

State Reducers (The Merge Strategy)

Reducers control how state updates merge when multiple nodes modify the same field. Default behavior is replace (new overwrites old), but you can use add for accumulation, add_messages for smart appending, or custom functions for domain-specific merge logic.

This diagram illustrates the critical problem reducers solve in LangGraph: what happens when multiple nodes update the same field?

The Scenario: Starting from {status: 'idle', attempts: 0}, two nodes run and both update the same fields. Node A sets attempts: 1, Node B sets attempts: 2.

Without Reducers (Left Path): The default “replace” behavior means the last update wins. You end up with attempts: 2, completely losing Node A’s contribution. If Node A represented one retry attempt, that count just disappeared from your state.

With Add Reducer (Right Path): By annotating the field as Annotated[int, add], you tell LangGraph to accumulate values instead of replacing them. Now you get attempts: 3 (the initial 0 + Node A’s 1 + Node B’s 2), preserving all contributions.

The Key Insight: Different fields need different merge strategies. status should use “replace” (you want the latest status, not accumulated statuses). attempts should use “add” (you want the total count, not just the last count). Reducers let you specify the right strategy per field, preventing silent data loss in your agent’s state.

Following are the two example reducers in Python.

Example 1: Reducers control merge behavior

from operator import add

from typing import Annotated

class SmartState(TypedDict):

# Replace (default): New value overwrites old

status: str

current_step: str

# Add: Accumulate values

total_tokens: Annotated[int, add]

total_cost: Annotated[float, add]

# Custom: Your logic

def merge_unique_urls(old: list, new: list) -> list:

"""Combine lists, remove duplicates."""

return list(set(old + new))

visited_urls: Annotated[list, merge_unique_urls]

# Messages: Smart appending (handles updates by ID)

messages: Annotated[Sequence[BaseMessage], add_messages]Example 2: When each reducer makes sense

# Replace: Most fields (status, current_step, task, error_message)

# You want the latest value, not accumulated values

# Add: Counters and accumulators

total_tokens: Annotated[int, add] # 100 + 50 = 150

total_cost: Annotated[float, add] # 0.002 + 0.003 = 0.005

# Custom: Domain-specific logic

# Example: Merge search results without duplicates

def merge_results(old: list[dict], new: list[dict]) -> list[dict]:

"""Merge search results, dedupe by URL."""

seen_urls = {r["url"] for r in old}

unique_new = [r for r in new if r["url"] not in seen_urls]

return old + unique_new

search_results: Annotated[list[dict], merge_results]

# add_messages: Special case for conversation

# Appends new messages, updates existing by ID

messages: Annotated[Sequence[BaseMessage], add_messages]State in Action: A Complete Example

from typing import TypedDict, Annotated, Sequence

from langchain_core.messages import BaseMessage, HumanMessage, AIMessage

from langgraph.graph import add_messages

from operator import add

class ProductionState(TypedDict):

"""Real-world state for a research agent."""

# User request

task: str

# Conversation

messages: Annotated[Sequence[BaseMessage], add_messages]

# Workflow tracking

current_step: str # "planning", "searching", "analyzing", "writing"

steps_completed: list[str]

# Retry logic

attempts: int

max_attempts: int

# Cost tracking

total_tokens: Annotated[int, add]

total_cost: Annotated[float, add]

# Search results

search_queries: list[str]

search_results: list[dict]

# Output

final_report: str | None

# Status

status: str # "running", "complete", "error", "needs_human"

error_message: str | None

# Initialize state

initial_state = ProductionState(

task="Research the latest developments in quantum computing",

messages=[HumanMessage(content="Research quantum computing")],

current_step="planning",

steps_completed=[],

attempts=0,

max_attempts=3,

total_tokens=0,

total_cost=0.0,

search_queries=[],

search_results=[],

final_report=None,

status="running",

error_message=None

)

# Node updates only what it needs to

def planning_node(state: ProductionState) -> dict:

"""Plan the research approach."""

# Node does work...

queries = ["quantum computing 2024", "quantum algorithms latest"]

# Return only updates (partial state)

return {

"search_queries": queries,

"current_step": "searching",

"steps_completed": state["steps_completed"] + ["planning"],

"total_tokens": 150, # This gets added to existing total

}After planning_node runs, state looks like:

{

"task": "Research the latest developments in quantum computing",

"messages": [HumanMessage(...)],

"current_step": "searching", # ← Updated

"steps_completed": ["planning"], # ← Updated

"attempts": 0,

"max_attempts": 3,

"total_tokens": 150, # ← Accumulated (was 0, now 150)

"total_cost": 0.0,

"search_queries": ["quantum computing 2024", ...], # ← Updated

"search_results": [],

"final_report": None,

"status": "running",

"error_message": None

}Key insights:

- Nodes return partial updates: Only the fields that changed

- Reducers merge intelligently:

total_tokensaccumulates,current_stepreplaces - State is always complete: Even if a node only updates one field, you get the full state

- Observable at every step: Inspect state after each node to see what happened

Nodes (Single-Purpose Workers / State Transformers)

Nodes transform state. That’s it. They receive state, do work, return updates. A well-designed node:

- Has a single, clear purpose

- Receives full state

- Returns partial updates

- Is stateless (no instance variables)

- Is deterministic (when possible)

The Anatomy of a Good Node through Python Code

from typing import TypedDict

def good_node(state: AgentState) -> dict:

"""

A well-designed node:

1. Has a single, clear purpose

2. Receives full state

3. Returns partial updates

4. Is stateless (no instance variables)

5. Is deterministic (when possible)

"""

# 1. Extract what you need from state

current_task = state["task"]

messages = state["messages"]

attempts = state["attempts"]

# 2. Do ONE thing well

result = perform_specific_work(current_task, messages)

# 3. Return only what changed

return {

"current_step": "next_step",

"attempts": attempts + 1,

"result_data": result,

}

# LangGraph merges this with existing state using reducersThe Three Core Node Patterns

Every production agent uses these three patterns. Master them and you’re 80% there.

Pattern 1: LLM Decision Node

Purpose: Let the LLM decide what to do next.

from langchain_openai import ChatOpenAI

from langchain_core.messages import SystemMessage

llm = ChatOpenAI(model="gpt-4o", temperature=0)

# Define tools the LLM can use

from langchain_core.tools import tool

@tool

def search_web(query: str) -> str:

"""Search the web for information."""

# Implementation here

return f"Search results for: {query}"

@tool

def calculate(expression: str) -> float:

"""Evaluate a mathematical expression."""

# Implementation here

return eval(expression)

tools = [search_web, calculate]

def agent_decision(state: AgentState) -> dict:

"""

LLM decides: call a tool, or provide final answer?

Returns:

- New AI message with tool calls OR final answer

- Updated current_step

"""

messages = state["messages"]

# Add system message for context

system_msg = SystemMessage(content="""

You are a helpful research assistant.

Use tools when you need information or calculations.

Provide a final answer when you have enough information.

""")

# Bind tools and invoke

llm_with_tools = llm.bind_tools(tools)

response = llm_with_tools.invoke([system_msg] + list(messages))

# Return updates

return {

"messages": [response], # add_messages appends this

"current_step": "routing",

"total_tokens": response.response_metadata.get("token_usage", {}).get("total_tokens", 0),

}What this node produces:

If LLM wants to call a tool:

AIMessage(content="", tool_calls=[{"name": "search_web", "args": {"query": "..."}}])If LLM has final answer:

AIMessage(content="Based on the information, here's the answer...")Why this is its own node:

- Checkpoint after LLM decision but before executing tools

- If tool execution fails, retry tools without re-prompting LLM

- Log what LLM decided vs. what actually happened

- Swap LLM models without touching tool execution

Pattern 2: Tool Execution Node

Purpose: Execute the tools the LLM decided to call.

from langgraph.prebuilt import ToolNode

# Option 1: Use the built-in ToolNode (recommended)

tool_node = ToolNode(tools)

# The ToolNode automatically:

# 1. Extracts tool calls from last message

# 2. Executes them (in parallel when possible)

# 3. Handles errors gracefully

# 4. Returns ToolMessage objects

# Option 2: Custom tool execution with error handling

def custom_tool_execution(state: AgentState) -> dict:

"""

Execute tools with custom error handling and retry logic.

"""

messages = state["messages"]

last_message = messages[-1]

tool_messages = []

for tool_call in last_message.tool_calls:

try:

# Find the tool

tool_name = tool_call["name"]

tool_args = tool_call["args"]

tool_func = {t.name: t for t in tools}[tool_name]

# Execute

result = tool_func.invoke(tool_args)

# Create success message

tool_messages.append(ToolMessage(

content=str(result),

tool_call_id=tool_call["id"],

name=tool_name,

))

except Exception as e:

# Create error message

tool_messages.append(ToolMessage(

content=f"Error executing {tool_name}: {str(e)}",

tool_call_id=tool_call["id"],

name=tool_name,

additional_kwargs={"error": True},

))

return {

"messages": tool_messages,

"current_step": "decision", # Loop back to LLM

}Why this is its own node:

- Tool execution can fail independently of LLM

- Different retry strategies: exponential backoff for tools, model switching for LLM

- Parallel execution when possible

- Rate limiting per tool

- Checkpoint after tools complete

Pattern 3: Validation Node

Purpose: Check if we’re done or need to retry.

def validate_result(state: AgentState) -> dict:

"""

Validate the agent's output.

Checks:

1. Do we have a final answer?

2. Is it high quality?

3. Does it address the original task?

"""

messages = state["messages"]

task = state["task"]

attempts = state["attempts"]

max_attempts = state["max_attempts"]

# Get last message

last_message = messages[-1]

# Check 1: Is there content (not just tool calls)?

if not last_message.content:

return {

"status": "needs_retry",

"error_message": "No final answer provided",

"attempts": attempts + 1,

}

# Check 2: Minimum length

if len(last_message.content) < 50:

return {

"status": "needs_retry",

"error_message": "Answer too brief",

"attempts": attempts + 1,

}

# Check 3: Contains key terms from task

task_keywords = set(task.lower().split())

answer_keywords = set(last_message.content.lower().split())

overlap = len(task_keywords & answer_keywords)

if overlap < 2:

return {

"status": "needs_retry",

"error_message": "Answer doesn't address task",

"attempts": attempts + 1,

}

# All checks passed

return {

"status": "complete",

"final_answer": last_message.content,

}

# Advanced: LLM-based validation

def llm_validate_result(state: AgentState) -> dict:

"""Use an LLM to validate quality."""

messages = state["messages"]

task = state["task"]

last_message = messages[-1]

validation_prompt = f"""

Task: {task}

Agent's answer: {last_message.content}

Is this answer:

1. Complete (addresses all parts of the task)?

2. Accurate (based on the tool results)?

3. Well-structured and clear?

Respond with JSON:

{{"valid": true/false, "reason": "explanation"}}

"""

validator_llm = ChatOpenAI(model="gpt-4o", temperature=0)

validation = validator_llm.invoke([HumanMessage(content=validation_prompt)])

import json

result = json.loads(validation.content)

if result["valid"]:

return {

"status": "complete",

"final_answer": last_message.content,

}

else:

return {

"status": "needs_retry",

"error_message": f"Validation failed: {result['reason']}",

"attempts": state["attempts"] + 1,

}Why this is its own node:

- Validation logic is independent and swappable

- Start simple (basic checks), upgrade to LLM validation

- Add human validation for critical tasks

- Test validation separately from decision/execution

Edges (Control Flow)

Edges connect nodes and control flow. They’re what makes graphs more powerful than chains.

Static Edges: Fixed Paths

from langgraph.graph import StateGraph, END

graph = StateGraph(AgentState)

# Add nodes

graph.add_node("plan", planning_node)

graph.add_node("execute", execution_node)

graph.add_node("summarize", summary_node)

# Static edges: always go from A → B

graph.add_edge("plan", "execute") # After planning, always execute

graph.add_edge("execute", "summarize") # After executing, always summarize

graph.add_edge("summarize", END) # After summarizing, we're doneUse static edges when the next step is always the same.

Conditional Edges: Decision Points

This is where the power comes in.

def route_after_decision(state: AgentState) -> str:

"""

Routing logic: decide which node runs next.

Returns a string that maps to a node name.

"""

messages = state["messages"]

last_message = messages[-1]

# Decision point: did LLM call tools?

if hasattr(last_message, "tool_calls") and last_message.tool_calls:

return "execute_tools"

else:

return "validate"

# Add conditional edge

graph.add_conditional_edges(

"agent_decision", # From this node

route_after_decision, # Use this function to decide

{

"execute_tools": "tools", # Map return value → node

"validate": "validate", # Map return value → node

}

)The routing function: - Receives full state - Returns a string - String maps to next node via the dictionary

Common Routing Patterns

Pattern 1: Binary Decision (Retry or Give Up)

def should_retry(state: AgentState) -> str:

"""Check if we should retry or fail."""

if state["attempts"] < state["max_attempts"]:

return "retry"

return "give_up"

graph.add_conditional_edges(

"validate",

should_retry,

{

"retry": "agent_decision", # Loop back

"give_up": "error_handler", # Handle failure

}

)Pattern 2: Multi-Way Routing (Task Type)

def route_by_task_type(state: AgentState) -> str:

"""Route to specialized nodes based on task type."""

task = state["task"].lower()

if "search" in task or "find" in task:

return "search_specialist"

elif "analyze" in task or "compare" in task:

return "analysis_specialist"

elif "write" in task or "create" in task:

return "generation_specialist"

else:

return "general_agent"

graph.add_conditional_edges(

"task_classifier",

route_by_task_type,

{

"search_specialist": "search_node",

"analysis_specialist": "analysis_node",

"generation_specialist": "generation_node",

"general_agent": "general_node",

}

)Pattern 4: Tool Call Routing

This is the most common pattern in agentic systems: “did the LLM decide to use tools, or does it have a final answer?”

def route_tools(state: AgentState) -> str:

"""Route based on whether LLM wants to use tools."""

messages = state["messages"]

last_message = messages[-1]

if hasattr(last_message, 'tool_calls') and last_message.tool_calls:

return "tools"

return "end"

graph.add_conditional_edges(

"agent",

route_tools,

{

"tools": "tool_execution",

"end": END

}

)Pattern 5: Validation-Based Routing

This pattern implements quality loops: try, validate, retry if needed. Essential for any agent that needs to meet quality standards.

def route_validation(state: AgentState) -> str:

"""Route based on validation outcome."""

is_valid = state.get("validation_passed", False)

attempts = state.get("attempts", 0)

if is_valid:

return "success"

elif attempts < 3:

return "retry"

else:

return "fail"

graph.add_conditional_edges(

"validate",

route_validation,

{

"success": "finalize",

"retry": "agent", # Loop back to try again

"fail": "error_handler"

}

)Pattern 6: Error Handling

Different errors need different handling. Don’t treat all failures the same way.

def route_by_error_type(state: AgentState) -> str:

"""Route based on error type and severity."""

error = state.get("error_message", "")

if "rate_limit" in error.lower():

return "backoff" # Wait and retry

elif "authentication" in error.lower():

return "refresh_auth" # Refresh credentials

elif "not_found" in error.lower():

return "fallback" # Try alternative approach

elif state["attempts"] < state["max_attempts"]:

return "retry" # Generic retry

else:

return "fail" # Give up

graph.add_conditional_edges(

"error_handler",

route_by_error_type,

{

"backoff": "exponential_backoff",

"refresh_auth": "auth_refresh",

"fallback": "alternative_approach",

"retry": "main_workflow",

"fail": "failure_node"

}

)Pattern 7: Multi-Stage Workflow

This pattern routes through a sequence of stages, where each stage does different work and might have different retry logic.

def route_workflow_stage(state: AgentState) -> str:

"""Route through multi-stage workflow."""

stage = state["current_stage"]

stage_map = {

"research": "research_node",

"analysis": "analysis_node",

"synthesis": "synthesis_node",

"review": "review_node"

}

return stage_map.get(stage, END)

graph.add_conditional_edges(

"coordinator",

route_workflow_stage,

{

"research_node": "research_node",

"analysis_node": "analysis_node",

"synthesis_node": "synthesis_node",

"review_node": "review_node",

END: END

}

)Pattern 8: Parallel Execution

Sometimes you need to do multiple things at once: make several API calls, process multiple documents, query multiple databases. Static routing does this sequentially. Parallel routing does it concurrently. LangGraph supports parallel node execution using Send:

from langgraph.graph import Send

def route_parallel(state: AgentState) -> list[Send]:

"""Execute multiple nodes in parallel."""

tasks = state["tasks"]

# Send each task to a worker node

return [

Send("worker", {"task": task, "task_id": i})

for i, task in enumerate(tasks)

]

graph.add_conditional_edges(

"dispatcher",

route_parallel

)Part 2: Execution Flow and Core Agent Pattern

Execution Flow (Putting It All Together)

Let’s build a complete agent from scratch.

from typing import TypedDict, Annotated, Sequence

from langchain_core.messages import BaseMessage, HumanMessage, SystemMessage

from langchain_openai import ChatOpenAI

from langgraph.graph import StateGraph, END, add_messages

from langgraph.prebuilt import ToolNode

from langchain_core.tools import tool

from operator import add

# 1. DEFINE STATE

class ResearchAgentState(TypedDict):

"""State for a research agent."""

messages: Annotated[Sequence[BaseMessage], add_messages]

task: str

current_step: str

attempts: int

max_attempts: int

total_tokens: Annotated[int, add]

final_answer: str | None

status: str

# 2. DEFINE TOOLS

@tool

def search_web(query: str) -> str:

"""Search the web for information."""

# Mock implementation

return f"Search results for '{query}': Recent advances in quantum computing include..."

@tool

def get_academic_papers(topic: str) -> str:

"""Get recent academic papers on a topic."""

# Mock implementation

return f"Recent papers on '{topic}': Paper 1: Title..., Paper 2: Title..."

tools = [search_web, get_academic_papers]

# 3. DEFINE NODES

llm = ChatOpenAI(model="gpt-4o", temperature=0)

def agent_decision(state: ResearchAgentState) -> dict:

"""LLM decides what to do next."""

messages = state["messages"]

system_prompt = SystemMessage(content="""

You are a research assistant. Use the available tools to gather information.

When you have enough information, provide a comprehensive answer.

""")

llm_with_tools = llm.bind_tools(tools)

response = llm_with_tools.invoke([system_prompt] + list(messages))

return {

"messages": [response],

"current_step": "routing",

"total_tokens": 100, # Mock token count

}

tool_node = ToolNode(tools)

def validate_result(state: ResearchAgentState) -> dict:

"""Check if we have a good answer."""

messages = state["messages"]

last_message = messages[-1]

attempts = state["attempts"]

# Check if we have an answer

if not last_message.content or len(last_message.content) < 100:

return {

"status": "needs_retry",

"attempts": attempts + 1,

}

return {

"status": "complete",

"final_answer": last_message.content,

}

# 4. DEFINE ROUTING

def route_after_decision(state: ResearchAgentState) -> str:

"""Route based on LLM decision."""

last_message = state["messages"][-1]

if hasattr(last_message, "tool_calls") and last_message.tool_calls:

return "execute"

return "validate"

def route_after_validation(state: ResearchAgentState) -> str:

"""Route based on validation result."""

if state["status"] == "complete":

return "end"

elif state["attempts"] < state["max_attempts"]:

return "retry"

return "end" # Max attempts reached

# 5. BUILD GRAPH

graph = StateGraph(ResearchAgentState)

# Add nodes

graph.add_node("decide", agent_decision)

graph.add_node("execute", tool_node)

graph.add_node("validate", validate_result)

# Set entry point

graph.set_entry_point("decide")

# Add edges

graph.add_conditional_edges(

"decide",

route_after_decision,

{

"execute": "execute",

"validate": "validate",

}

)

graph.add_edge("execute", "decide") # Loop back after tools

graph.add_conditional_edges(

"validate",

route_after_validation,

{

"end": END,

"retry": "decide",

}

)

# 6. COMPILE

app = graph.compile()

# 7. RUN

initial_state = {

"messages": [HumanMessage(content="What are the latest developments in quantum computing?")],

"task": "Research quantum computing",

"current_step": "start",

"attempts": 0,

"max_attempts": 3,

"total_tokens": 0,

"final_answer": None,

"status": "running",

}

# Execute

final_state = app.invoke(initial_state)

print("Final Answer:", final_state["final_answer"])

print("Total Tokens:", final_state["total_tokens"])

print("Attempts:", final_state["attempts"])What Happens When This Runs

Execution trace:

Step 1: DECIDE node

Input state: initial_state

LLM decides to call search_web tool

Output: {"messages": [AIMessage with tool_call], ...}

Router: sees tool_calls → routes to EXECUTE

Step 2: EXECUTE node

Input state: updated state with tool_call

Runs search_web("quantum computing")

Output: {"messages": [ToolMessage with results], ...}

Static edge → routes to DECIDE

Step 3: DECIDE node (again)

Input state: state with search results

LLM sees results, decides to call get_academic_papers

Output: {"messages": [AIMessage with tool_call], ...}

Router: sees tool_calls → routes to EXECUTE

Step 4: EXECUTE node (again)

Input state: state with new tool_call

Runs get_academic_papers("quantum computing")

Output: {"messages": [ToolMessage with papers], ...}

Static edge → routes to DECIDE

Step 5: DECIDE node (third time)

Input state: state with all research data

LLM has enough info, provides final answer

Output: {"messages": [AIMessage with answer], ...}

Router: no tool_calls → routes to VALIDATE

Step 6: VALIDATE node

Input state: state with final answer

Checks answer quality (length > 100)

Passes validation

Output: {"status": "complete", "final_answer": "..."}

Router: status == "complete" → routes to END

Step 7: END

Execution stops, returns final stateKey observations:

- State flows through: Each node receives complete state, returns partial updates

- Routing is explicit: You can see exactly why each node was chosen

- Loops work naturally: DECIDE ↔︎ EXECUTE loop runs until LLM is satisfied

- Checkpointing is implicit: After each node, state is saved

- Observable: You could log state after each node to see evolution

Core Agent Pattern (Decide → Execute → Validate)

This is the heartbeat of production AI agents. Master this pattern and you’ve mastered 80% of what you need to build real-world agentic systems.

Every LangGraph agent, from simple task executors to complex research systems, follows this same three-node loop. It’s not arbitrary—this pattern emerged from thousands of production deployments as the optimal balance between flexibility and control.

The Three Nodes

1. DECIDE (The Brain)

The LLM Decision Node is where your agent thinks. It looks at everything that’s happened so far—the conversation history, tool results, previous attempts—and decides what to do next.

from langchain_openai import ChatOpenAI

from langchain_core.messages import SystemMessage

llm = ChatOpenAI(model="gpt-4o", temperature=0)

def decide_node(state: AgentState) -> dict:

"""

The brain: LLM decides the next action.

Possible outcomes:

1. Call a tool (search, calculate, email, etc.)

2. Provide a final answer

3. Ask for clarification

"""

messages = state["messages"]

# Context for the LLM

system_msg = SystemMessage(content="""

You are a helpful assistant with access to tools.

Use tools when you need information or to take actions.

When you have enough information, provide a clear final answer.

""")

# Bind tools and get decision

llm_with_tools = llm.bind_tools(tools)

response = llm_with_tools.invoke([system_msg] + list(messages))

# Return state updates

return {

"messages": [response],

"current_step": "routing",

}What this node does:

- Reads the entire conversation history from

state["messages"] - Considers available tools and their descriptions

- Makes a decision: call a tool OR provide a final answer

- Returns an AIMessage with either

tool_calls(actions to take) orcontent(final answer)

Why this is separate from execution: You want to checkpoint after the LLM decides but before executing tools. If a tool fails (network timeout, API error, rate limit), you can retry just the tool without burning tokens on another LLM call. In production, separating decision from execution cuts costs by 30-40% on retry scenarios.

2. EXECUTE (The Hands)

The Tool Execution Node does what the LLM decided. If the LLM said “search for X,” this node runs the search. If it said “calculate Y,” this node runs the calculation.

from langgraph.prebuilt import ToolNode

from langchain_core.tools import tool

# Define tools

@tool

def search_web(query: str) -> str:

"""Search the web for current information."""

# Implementation here

return f"Search results for: {query}"

@tool

def calculator(expression: str) -> float:

"""Evaluate a mathematical expression."""

import ast

import operator

# Safe evaluation of math expressions

ops = {

ast.Add: operator.add,

ast.Sub: operator.sub,

ast.Mult: operator.mul,

ast.Div: operator.truediv,

}

def eval_expr(node):

if isinstance(node, ast.Num):

return node.n

elif isinstance(node, ast.BinOp):

return ops[type(node.op)](eval_expr(node.left), eval_expr(node.right))

raise ValueError(f"Unsupported expression: {node}")

tree = ast.parse(expression, mode='eval')

return eval_expr(tree.body)

tools = [search_web, calculator]

# Use LangGraph's built-in ToolNode

execute_node = ToolNode(tools)

# That's it! ToolNode automatically:

# - Extracts tool calls from the last message

# - Executes them (in parallel when possible)

# - Handles errors gracefully

# - Returns ToolMessage objects with resultsWhat ToolNode does automatically:

Looks at the last message in

state["messages"]Finds all

tool_callsin that messageFor each tool call:

- Matches the tool name to your tool functions

- Extracts the arguments

- Executes the tool (with error handling)

- Creates a ToolMessage with the result

Returns all ToolMessages to add to state

Why this is separate from decision: Tool execution has different failure modes than LLM calls. Network timeouts, API rate limits, invalid parameters—these need different retry strategies. By isolating tool execution, you can:

- Retry failed tools without re-running the LLM

- Implement per-tool rate limiting

- Run multiple tools in parallel

- Add tool-specific error handling

3. VALIDATE (The Quality Control)

The Validation Node checks if we’re done or need to try again. This is what separates toy demos from production systems.

def validate_node(state: AgentState) -> dict:

"""

Quality control: are we done?

Checks:

1. Do we have a final answer?

2. Is it high quality?

3. Does it address the original task?

"""

messages = state["messages"]

task = state["task"]

attempts = state["attempts"]

max_attempts = state["max_attempts"]

last_message = messages[-1]

# Check 1: Is there content (not just tool calls)?

if not last_message.content:

return {

"status": "needs_retry",

"error_message": "No final answer provided",

"attempts": attempts + 1,

}

# Check 2: Minimum quality bar (length check)

if len(last_message.content) < 100:

return {

"status": "needs_retry",

"error_message": "Answer too brief, needs more detail",

"attempts": attempts + 1,

}

# Check 3: Relevance check (basic keyword matching)

task_words = set(task.lower().split())

answer_words = set(last_message.content.lower().split())

overlap = len(task_words & answer_words)

if overlap < 2:

return {

"status": "needs_retry",

"error_message": "Answer doesn't address the original task",

"attempts": attempts + 1,

}

# All checks passed!

return {

"status": "complete",

"final_answer": last_message.content,

}What makes good validation:

Start simple, then upgrade:

Level 1: Basic checks (shown above)

- Does an answer exist?

- Is it long enough?

- Does it contain task keywords?

Level 2: LLM-based validation

def llm_validate_node(state: AgentState) -> dict:

"""Use an LLM to judge quality."""

validator = ChatOpenAI(model="gpt-4o-mini", temperature=0)

validation_prompt = f"""

Task: {state['task']}

Answer: {state['messages'][-1].content}

Is this answer:

1. Complete (addresses all parts)?

2. Accurate (based on tool results)?

3. Well-structured?

Respond with JSON: {{"valid": true/false, "reason": "..."}}

"""

result = validator.invoke([HumanMessage(content=validation_prompt)])

import json

validation = json.loads(result.content)

if validation["valid"]:

return {"status": "complete", "final_answer": state["messages"][-1].content}

else:

return {

"status": "needs_retry",

"error_message": f"Validation failed: {validation['reason']}",

"attempts": state["attempts"] + 1,

}Level 3: Human validation (for critical decisions)

def human_validate_node(state: AgentState) -> dict:

"""Pause for human review."""

return {

"status": "needs_human_review",

"current_step": "awaiting_approval",

}

# Use with interrupt_before in compilation:

# app = graph.compile(checkpointer=memory, interrupt_before=["validate"])Why validation is its own node: You want to swap validation strategies without touching decision or execution logic. Start with basic checks in development, upgrade to LLM validation in staging, add human review for production. By keeping validation separate, these changes don’t ripple through your entire codebase.

The Routing Logic

Now let’s connect these three nodes with conditional edges. This is where the pattern comes alive.

from langgraph.graph import StateGraph, END

from typing import Annotated, Sequence

from langchain_core.messages import BaseMessage

from langgraph.graph import add_messages

# State definition

class AgentState(TypedDict):

messages: Annotated[Sequence[BaseMessage], add_messages]

task: str

current_step: str

attempts: int

max_attempts: int

status: str

final_answer: str | None

error_message: str | None

# Build the graph

graph = StateGraph(AgentState)

# Add the three core nodes

graph.add_node("decide", decide_node)

graph.add_node("execute", execute_node)

graph.add_node("validate", validate_node)

# Set entry point

graph.set_entry_point("decide")Router 1: After DECIDE - Tool calls present?

def route_after_decide(state: AgentState) -> str:

"""

Decision point: did the LLM call tools or provide an answer?

Returns:

"execute" - if tool calls present

"validate" - if final answer provided

"""

last_message = state["messages"][-1]

# Check for tool calls

if hasattr(last_message, "tool_calls") and last_message.tool_calls:

return "execute"

# No tools means we have a final answer

return "validate"

graph.add_conditional_edges(

"decide",

route_after_decide,

{

"execute": "execute",

"validate": "validate",

}

)This router implements the first branching logic: if the LLM wants to use tools, go execute them. If the LLM provided a final answer, skip execution and validate it.

Always loop back after EXECUTE

# After executing tools, ALWAYS return to DECIDE

graph.add_edge("execute", "decide")This is the core loop. After tools run, the LLM needs to see the results and decide what to do next. Maybe it needs more information (call another tool). Maybe it has enough to answer. The LLM decides based on the tool results now in the message history.

This loop runs as many times as needed:

- LLM: “Search for X” → Execute → Results added

- LLM: “Search for Y too” → Execute → More results added

- LLM: “Calculate Z” → Execute → Calculation added

- LLM: “Here’s the answer based on all that data” → Validate

Router 2: After VALIDATE - Valid and complete?

def route_after_validate(state: AgentState) -> str:

"""

Decision point: is the answer good enough?

Returns:

"end" - if complete or max attempts reached

"retry" - if invalid and retries remaining

"""

status = state["status"]

# Success case

if status == "complete":

return "end"

# Check retry budget

if state["attempts"] < state["max_attempts"]:

return "retry"

# Max attempts exhausted

return "end"

graph.add_conditional_edges(

"validate",

route_after_validate,

{

"end": END,

"retry": "decide",

}

)This router implements the retry loop: if validation fails but we have attempts left, loop back to DECIDE. The LLM will see the validation error in the message history and try a different approach. If we hit max attempts, gracefully exit even if the answer isn’t perfect.

Router 3: After second validation check - Retries left?

This is shown in the diagram but handled within Router 2 above. The logic is:

- If valid → END (success path)

- If invalid but attempts < max → retry (back to DECIDE)

- If invalid and attempts >= max → END (failure path, but fail gracefully)

Compile and Execute

# Compile the graph

app = graph.compile()

# Run it

initial_state = {

"messages": [HumanMessage(content="What's the weather in San Francisco and what's 15% of 72?")],

"task": "Weather and calculation query",

"current_step": "start",

"attempts": 0,

"max_attempts": 3,

"status": "running",

"final_answer": None,

"error_message": None,

}

final_state = app.invoke(initial_state)

print("Final Answer:", final_state["final_answer"])

print("Total Attempts:", final_state["attempts"])Execution Trace: Following the Flow

Let’s trace what happens when you run this agent:

Iteration 1: First Tool Call

1. DECIDE node

- LLM sees: "What's the weather in SF and what's 15% of 72?"

- Decision: Call search_web("weather San Francisco")

- State update: messages += [AIMessage(tool_calls=[...])]

2. Router 1: Tool calls present? YES

- Route to EXECUTE

3. EXECUTE node

- Runs search_web tool

- Gets: "Current weather: 65°F, partly cloudy"

- State update: messages += [ToolMessage(content="Current weather...")]

4. Static edge: Always back to DECIDEIteration 2: Second Tool Call

5. DECIDE node

- LLM sees: original question + weather results

- Decision: Still need to calculate 15% of 72

- Calls calculator("72 * 0.15")

- State update: messages += [AIMessage(tool_calls=[...])]

6. Router 1: Tool calls present? YES

- Route to EXECUTE

7. EXECUTE node

- Runs calculator tool

- Gets: 10.8

- State update: messages += [ToolMessage(content="10.8")]

8. Static edge: Back to DECIDEIteration 3: Final Answer

9. DECIDE node

- LLM sees: question + weather + calculation

- Decision: Have all info, provide answer

- Response: "The weather in SF is 65°F and partly cloudy. 15% of 72 is 10.8."

- State update: messages += [AIMessage(content="The weather...")]

10. Router 1: Tool calls present? NO

- Route to VALIDATE

11. VALIDATE node

- Check 1: Content exists? YES

- Check 2: Length > 100? YES (assuming full answer)

- Check 3: Keywords present? YES ("weather", "72")

- State update: status = "complete", final_answer = "..."

12. Router 2: Valid and complete? YES

- Route to END

13. END: Return final stateWhy This Pattern Works in Production

Separation of Concerns

- Decision logic in DECIDE

- Execution logic in EXECUTE

- Validation logic in VALIDATE

- Change one without touching others

Retry at the Right Level

- LLM errors? Retry from DECIDE

- Tool errors? Retry from EXECUTE

- Quality issues? Retry the whole loop

- Each failure mode has the right recovery strategy

Observable Execution Every step is explicit:

# Add logging to see what's happening

def decide_node(state: AgentState) -> dict:

print(f"[DECIDE] Attempt {state['attempts']}")

result = # ... node logic

print(f"[DECIDE] Decision: {result}")

return resultYou can see exactly what the agent is thinking at each step. No black boxes.

Checkpointed Progress

from langgraph.checkpoint.memory import MemorySaver

memory = MemorySaver()

app = graph.compile(checkpointer=memory)

# If execution crashes after EXECUTE, resume from DECIDE

# The tool results are already in state—no duplicate workAfter each node, state is saved. If the system crashes, you resume from the last successful checkpoint. This prevents duplicate LLM calls and duplicate tool executions, saving both time and money.

Built-in Quality Loops

The retry mechanism is explicit: - Validation fails → increment attempts → loop back - Max attempts reached → stop gracefully - No infinite loops, no hanging processes

Flexible and Extensible

Need human-in-the-loop? Add it at VALIDATE:

app = graph.compile(

checkpointer=memory,

interrupt_before=["validate"] # Pause here

)Need different validation for different tasks? Replace the node:

graph.add_node("validate_code", code_validator)

graph.add_node("validate_writing", writing_validator)

# Route based on task type

def route_to_validator(state):

return "validate_code" if "code" in state["task"] else "validate_writing"Key Takeaways

This three-node pattern is the foundation. Real production agents add more nodes (planning, formatting, error handling, human review), but the core loop stays the same: decide what to do, do it, check if it’s good enough.

The routers are critical. Static edges (EXECUTE → DECIDE) create the tool-use loop. Conditional edges (after DECIDE, after VALIDATE) implement branching and retry logic. Together, they give you full control over agent behavior.

State flows through everything. Each node receives complete state, returns partial updates. Reducers merge the updates. The result is always a complete, consistent state you can inspect at any point.

Checkpointing is invisible but essential. After each node, state is saved. If anything fails, you resume from the last successful step. This isn’t something you have to think about—it just works.

Start here, then extend. Build your first agent with exactly these three nodes. Once you understand how they work together, you’ll know where to add more nodes (before DECIDE for planning, after VALIDATE for formatting, parallel to EXECUTE for concurrent operations). But you always come back to this pattern: think, act, verify.

This is production AI. Not because it’s complicated, but because it’s controlled, observable, and recoverable. That’s what separates toys from tools.

Checkpointing & Retries

This is the difference between a demo and a production system. Checkpointing saves state after each step so you can resume from failures. Retries let you handle transient errors without starting over.

In the real world, things fail. APIs timeout. Networks drop. Rate limits hit. LLMs hallucinate. If your agent can’t handle these failures gracefully, it’s not production-ready. Checkpointing and retries are how you build resilience into your agents—the ability to survive failures, learn from them, and keep going.

Think about it: if your agent spends 5 minutes and $2 in API calls getting to step 8 of a 10-step workflow, then hits a network timeout, do you really want to start over from step 1? No. You want to save progress, retry the failed step, and continue. That’s what checkpointing gives you.

Why Checkpointing Matters

Checkpointing is automatic progress saving. After each node executes, LangGraph saves the current state to a checkpointer. If execution fails, you can resume from the last successful checkpoint instead of restarting from scratch.

This isn’t just about error recovery—it’s also about human-in-the-loop workflows. Save state, wait for human approval, resume. Save state, pause for 24 hours, resume. Save state, inspect intermediate results, modify if needed, resume. None of this works without checkpointing.

Without checkpointing:

# Long workflow

graph.invoke(state)

# ❌ Network error on step 8 of 10

# Must restart from beginningYou lose all progress. The 7 successful steps? Gone. The API calls you paid for? Wasted. The intermediate results? Lost. You start over, hit the same APIs again, hope the network is better this time. This is fine for demos, unacceptable for production.

With checkpointing:

# Save state after each step

checkpointer = MemorySaver()

graph = graph.compile(checkpointer=checkpointer)

# Resume from last successful checkpoint

result = graph.invoke(state, config={"thread_id": "abc123"})

# ✅ Resumes from step 8Now you have resilience. Step 7 succeeded and saved a checkpoint. Step 8 failed. You resume from the checkpoint, retry step 8, and continue. No lost progress, no wasted API calls, no starting over.

The thread_id is the key—it identifies this specific workflow instance. Same thread_id = same checkpoint history. Different thread_id = different workflow, different checkpoints. Think of it as a conversation ID or workflow instance ID.

Implementing Checkpointing

Checkpointing in LangGraph is straightforward: create a checkpointer, compile your graph with it, and pass a thread_id when invoking. LangGraph handles the rest—saving state after each node, loading state when resuming, managing the checkpoint history.

Basic Setup

The simplest checkpointer is MemorySaver—it stores checkpoints in memory. Great for development and testing, but checkpoints disappear when the process exits. For production, you’ll use persistent checkpointers (SQLite, PostgreSQL) that survive restarts.

from langgraph.checkpoint.memory import MemorySaver

# Create checkpointer

checkpointer = MemorySaver()

# Compile graph with checkpointing

app = graph.compile(checkpointer=checkpointer)

# Execute with thread ID (identifies the conversation/workflow)

config = {"configurable": {"thread_id": "conversation-123"}}

result = app.invoke(initial_state, config=config)What happens here:

- Graph executes node by node

- After each node completes, LangGraph saves the current state to the checkpointer

- The checkpoint is tagged with the thread_id (“conversation-123”)

- If execution fails, you can resume by invoking with the same thread_id

The config dictionary is how you pass runtime parameters to LangGraph. The configurable key holds things like thread_id that control execution behavior. You can also pass other config like recursion limits, timeouts, etc.

Streaming with Checkpoints

Streaming execution lets you see progress as it happens, node by node. Combined with checkpointing, you get both visibility and resilience—watch the agent work in real-time, and if it fails, you can resume from the last checkpoint.

# Stream execution with automatic checkpointing

for chunk in app.stream(initial_state, config=config):

print(f"Step: {chunk}")

# State is automatically saved after each stepEach chunk is the output of one node execution. You can log it, display it to users, save it to a database—whatever you need. Meanwhile, LangGraph is checkpointing after each node in the background.

Why this matters: For long-running workflows, streaming gives users feedback that something is happening. For debugging, it shows you exactly where execution is in real-time. For monitoring, it lets you track progress and detect stalls.

Resuming from Checkpoint

The real power of checkpointing: resuming from where you left off. If execution fails, you don’t need to replay the entire workflow—just resume from the last checkpoint.

# Get checkpoint state

state = app.get_state(config)

print(f"Current state: {state}")

# Resume execution

result = app.invoke(None, config=config) # None = use saved stateHow resumption works:

get_state(config)retrieves the last checkpoint for this thread_id- You can inspect it, modify it, or just verify it’s what you expect

invoke(None, config)says “don’t use new initial state—load from checkpoint”- LangGraph loads the checkpoint and resumes execution from the next node

When to resume:

- After a crash or exception

- After a planned pause (human-in-the-loop)

- After inspecting intermediate state and deciding to continue

- After modifying state and wanting to retry with the changes

Pro tip: You can also get the full checkpoint history with get_state_history(config), which returns all checkpoints for this thread, not just the latest. Useful for debugging or replaying execution step by step.

Retry Mechanisms

Checkpointing handles the “save progress” part. Retries handle the “try again when things fail” part. Together, they make your agents resilient: save state, fail, retry, succeed, continue.

There are three main retry patterns, each suited to different failure modes. Simple retry counters work for flaky operations. Exponential backoff works for rate limits and overloaded services. Error-specific strategies work when different errors need different handling.

Pattern 1: Retry Counter in State

The simplest retry mechanism: track how many times you’ve tried, and give up after N attempts. Works for operations that might fail occasionally but usually succeed—network calls, flaky APIs, non-deterministic operations.

class AgentState(TypedDict):

messages: list

retry_count: int

max_retries: int

last_error: str | None

def agent_with_retry(state: AgentState) -> dict:

try:

# Attempt operation

result = risky_operation()

return {

"messages": [result],

"retry_count": 0 # Reset on success

}

except Exception as e:

return {

"retry_count": state["retry_count"] + 1,

"last_error": str(e)

}

def route_retry(state: AgentState) -> str:

if state["retry_count"] >= state["max_retries"]:

return "fail"

elif state["last_error"]:

return "retry"

else:

return "continue"

graph.add_conditional_edges(

"agent",

route_retry,

{

"retry": "agent", # Loop back

"fail": "error_handler",

"continue": "next_step"

}

)How this works:

- Node tries the operation

- If it succeeds, reset retry_count to 0 and continue

- If it fails, increment retry_count and save the error

- Router checks: have we exceeded max_retries?

- If yes → route to error handler (give up)

- If no → route back to the same node (try again)

Why reset retry_count on success? Because retries are per-operation, not per-workflow. If step 3 fails twice then succeeds, and later step 7 fails, you want step 7 to get its own 3 retries. Resetting on success ensures each operation gets a fresh retry budget.

When to use this: Flaky network calls, occasional API errors, operations that usually work but sometimes don’t. Not suitable for systematic failures (bad credentials, invalid inputs) that will never succeed no matter how many times you retry.

Pattern 2: Exponential Backoff

Some failures aren’t truly random—they’re caused by temporary overload or rate limiting. Retrying immediately just hammers the struggling service. Exponential backoff waits between retries, with the wait time doubling each time: 1s, 2s, 4s, 8s, 16s.

import time

from datetime import datetime, timedelta

class AgentState(TypedDict):

retry_count: int

last_attempt: datetime | None

backoff_seconds: int

def agent_with_backoff(state: AgentState) -> dict:

# Check if we should wait before retrying

if state["last_attempt"]:

wait_time = timedelta(seconds=state["backoff_seconds"])

if datetime.now() - state["last_attempt"] < wait_time:

time.sleep(state["backoff_seconds"])

try:

result = risky_operation()

return {

"result": result,

"retry_count": 0,

"backoff_seconds": 1 # Reset backoff

}

except Exception as e:

return {

"retry_count": state["retry_count"] + 1,

"last_attempt": datetime.now(),

"backoff_seconds": min(state["backoff_seconds"] * 2, 60), # Exponential

"last_error": str(e)

}How exponential backoff works:

- First failure: wait 1 second before retry

- Second failure: wait 2 seconds

- Third failure: wait 4 seconds

- Fourth failure: wait 8 seconds

- Continues doubling up to a maximum (60 seconds here)

Why this works: It gives overloaded services time to recover. It backs off progressively so you’re not constantly hammering a rate-limited API. It’s self-adjusting—if the service recovers quickly, you retry quickly; if it’s slow to recover, you wait longer.

When to use this: Rate-limited APIs, overloaded services, database connection pools, any resource that experiences temporary capacity issues. Especially important for production systems where retry storms (thousands of clients all retrying at once) can make outages worse.

Production note: Add jitter (random variation) to backoff times to prevent thundering herd problems where all clients retry at exactly the same time. Example: instead of waiting exactly 4 seconds, wait 4 ± random(0, 1) seconds.

Pattern 3: Different Retry Strategies

Not all errors are created equal. A timeout might work if you retry. A rate limit needs exponential backoff. An authentication error needs credential refresh. Invalid input needs fixing, not retrying. Smart retry routing handles each error type appropriately.

def route_retry_strategy(state: AgentState) -> str:

"""Choose retry strategy based on error type."""

error = state["last_error"]

retry_count = state["retry_count"]

if retry_count >= 5:

return "fail"

# Different strategies for different errors

if "timeout" in error.lower():

return "retry_with_backoff"

elif "rate_limit" in error.lower():

return "retry_with_long_wait"

elif "invalid_input" in error.lower():

return "fix_input_and_retry"

else:

return "retry_immediate"

graph.add_conditional_edges(

"execution",

route_retry_strategy,

{

"retry_with_backoff": "exponential_backoff_node",

"retry_with_long_wait": "wait_60s_node",

"fix_input_and_retry": "input_fixer_node",

"retry_immediate": "execution", # Immediate retry

"fail": "error_handler"

}

)How this works:

- Operation fails and saves error message in state

- Router examines the error message to classify the error type

- Based on error type, routes to appropriate retry strategy:

- Timeout → exponential backoff (service might be slow)

- Rate limit → long wait (need to respect rate limits)

- Invalid input → fix the input before retrying

- Unknown error → immediate retry (might be transient)

Why this is better than generic retry: Because different errors have different solutions. Retrying invalid input 10 times won’t help—you need to fix the input. Immediately retrying a rate-limited request will just get you rate-limited again—you need to wait. This pattern routes each error to the appropriate recovery strategy.

Production pattern: Maintain structured error types, not just string messages. Instead of parsing “error: timeout occurred”, use error codes or exception types that you can match on reliably. Parse API error responses to extract error codes, retry-after headers, etc.

Extension: Add error-specific context to help recovery. For invalid input, save what was invalid. For rate limits, save when you can retry (from the Retry-After header). For auth errors, trigger credential refresh. Each error type gets specialized handling.

Production Checkpointing

MemorySaver is great for development, but production needs persistence. If your process crashes or restarts, memory is gone. Production checkpointers write to databases—SQLite for single-node deployments, PostgreSQL for distributed systems.

For production, use persistent checkpointers:

from langgraph.checkpoint.sqlite import SqliteSaver

# SQLite-based checkpointing

checkpointer = SqliteSaver.from_conn_string("checkpoints.db")

# PostgreSQL (for production)

from langgraph.checkpoint.postgres import PostgresSaver

checkpointer = PostgresSaver.from_conn_string("postgresql://...")

# Compile with persistent checkpointer

app = graph.compile(checkpointer=checkpointer)SQLite vs PostgreSQL:

SQLite - Good for single-machine deployments, moderate scale, simple setup. The checkpoint database is just a file on disk. Fast, reliable, no separate database server needed. Works great up to thousands of concurrent workflows.

PostgreSQL - Required for distributed deployments, high scale, multi-region. Multiple machines can share the same checkpoint database. Supports transactions, replication, backups. Necessary when you’re running agents across multiple servers.

Benefits of persistent checkpointing:

- Survives process restarts: Deploy new code, restart servers, workflows resume automatically

- Enables distributed execution: Multiple workers can coordinate using shared checkpoint storage

- Audit trail of all state transitions: Every checkpoint is saved, so you can replay execution, debug issues, understand what happened

- Easy debugging and inspection: Query the checkpoint database to see current state of all workflows, find stuck workflows, analyze execution patterns

Production considerations:

Checkpoint retention: Decide how long to keep checkpoints. Keep them forever for audit? Delete after workflow completes? Archive old checkpoints to cold storage? Depends on your compliance and debugging needs.

Checkpoint cleanup: Implement garbage collection for completed workflows. Otherwise your checkpoint database grows unbounded as workflows complete but their checkpoints remain.

Monitoring: Track checkpoint database size, query performance, failed checkpoint saves. A slow or full checkpoint database will stall all your agents.

Backup and recovery: Checkpoint database is critical infrastructure—if you lose it, all in-flight workflows are lost. Back it up regularly.

Thread ID strategy: Use meaningful thread IDs that you can track: user-{user_id}-session-{session_id}, workflow-{workflow_id}, etc. Random UUIDs work but make debugging harder.

Key Takeaways:

Checkpointing is mandatory for production. Without it, every failure means starting over. With it, you resume from the last successful step.

Retries handle transient failures. Network blips, API timeouts, rate limits—most failures are temporary. Smart retry logic turns failures into eventual success.

Different errors need different strategies. Don’t retry everything the same way. Timeout? Backoff. Rate limit? Wait. Invalid input? Fix it. Match strategy to error type.

Use persistent checkpointers in production. Memory checkpoints vanish on restart. SQLite/PostgreSQL checkpoints survive everything.

Combine checkpointing + retries for resilience. Checkpointing saves progress. Retries handle failures. Together they make agents that work reliably in the real world.

Exercise: Build a Research Agent with Deterministic Flow

Time to build something real. You’ll create a multi-stage research agent that demonstrates everything we’ve covered: explicit state, conditional routing, checkpointing, and retry logic.

This isn’t a toy. It’s a pattern you can use for production agents—the kind that run for minutes or hours, need to handle failures gracefully, and let you see exactly what’s happening at each step.

This exercise brings together everything from this module into one working system. You’ll see how state management, nodes, edges, checkpointing, and retries combine to create a resilient, observable agent. By the end, you’ll have a complete research agent that you can actually use, modify, and deploy.

Why this exercise matters: Most tutorials show isolated features. This shows how they work together in a real system. You’ll encounter the same challenges you’d face in production: handling failures, managing state across multiple steps, deciding when to retry vs fail, and maintaining observability. The patterns you learn here apply to any complex agent workflow.

Github Codebase URL: https://github.com/ranjankumar-gh/building-real-world-agentic-ai-systems-with-langgraph-codebase/tree/main/module-03

A complete reference implementation is available at the above url. This has production-ready code demonstrating concepts learned in this chapter / module. It includes working examples, tests, and documentation. Download and run in under five minutes to see explicit state management, deterministic flow, checkpointing, and retry logic in action.

What You’re Building

A research agent that:

- Takes a research query

- Plans search queries

- Executes searches (with retry on failure)

- Validates results (loops back if insufficient)

- Synthesizes findings

- Generates a final report

With full observability, checkpointing, and error handling.

The agent workflow:

Stage 1 - Planning: The LLM analyzes your research query and breaks it down into specific search queries. Instead of searching for “quantum computing,” it generates targeted queries like “quantum computing breakthroughs 2024” and “commercial quantum computing applications.”

Stage 2 - Searching: Execute the search queries using a real search tool. Each search might succeed or fail—network issues, API limits, bad queries. The agent collects whatever results it can get.

Stage 3 - Validating: Check if we got enough valid results to proceed. If yes, move to processing. If no, increment retry counter and decide whether to retry searches or give up.

Stage 4 - Processing: Extract key findings from the search results. The LLM analyzes all the results and pulls out the most important, relevant facts.

Stage 5 - Generating: Synthesize findings into a structured report with executive summary, key points, and conclusion.

Error Handling: At any point, if something fails and we haven’t exceeded max retries, loop back and try again. If we have exceeded retries, fail gracefully with an error report.

Why this structure? Each stage is a separate node with a clear responsibility. If search fails, you retry just the search—not the planning. If validation fails, you can either retry search or adjust your validation criteria. The separation makes debugging easy and retries efficient.

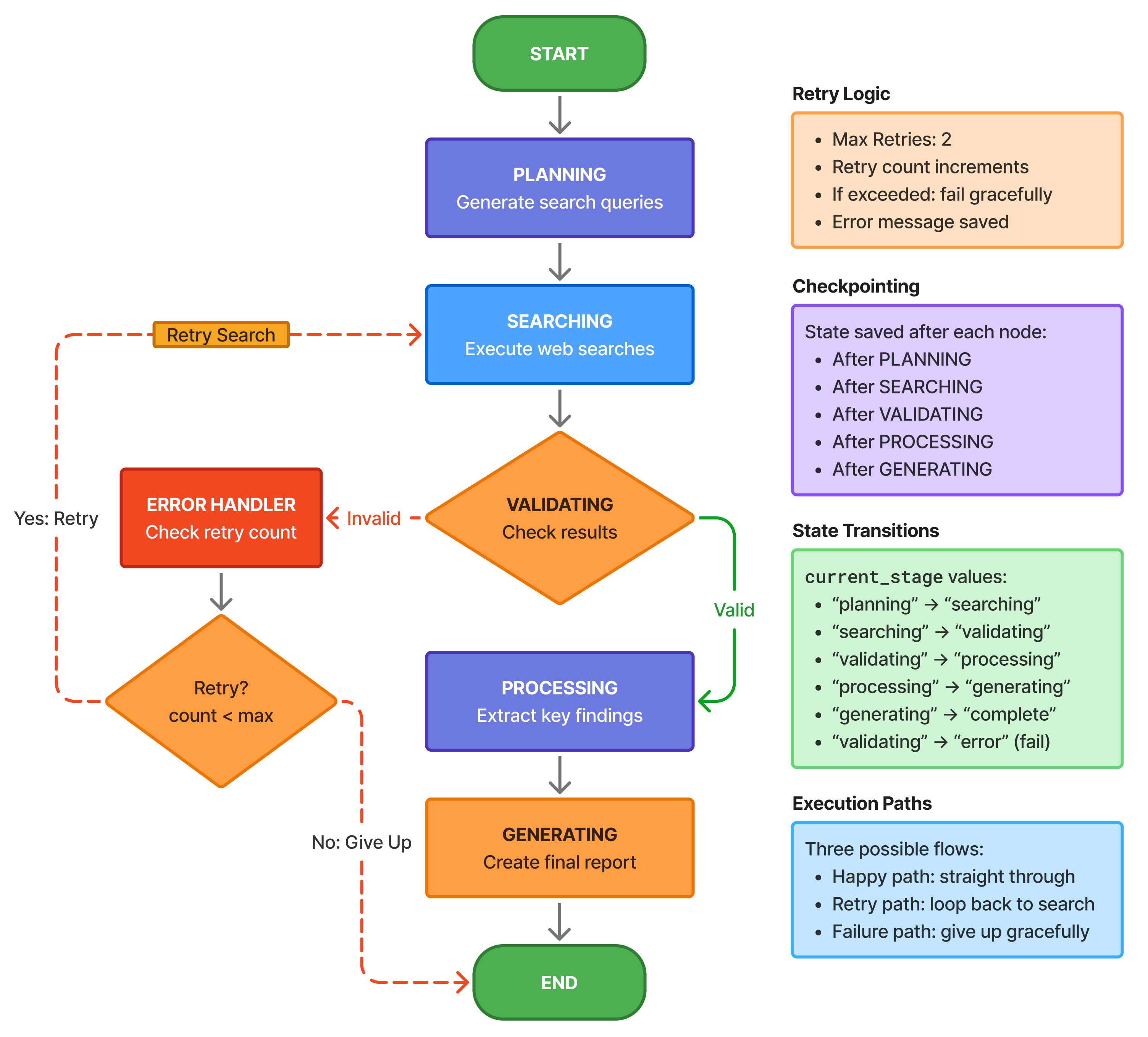

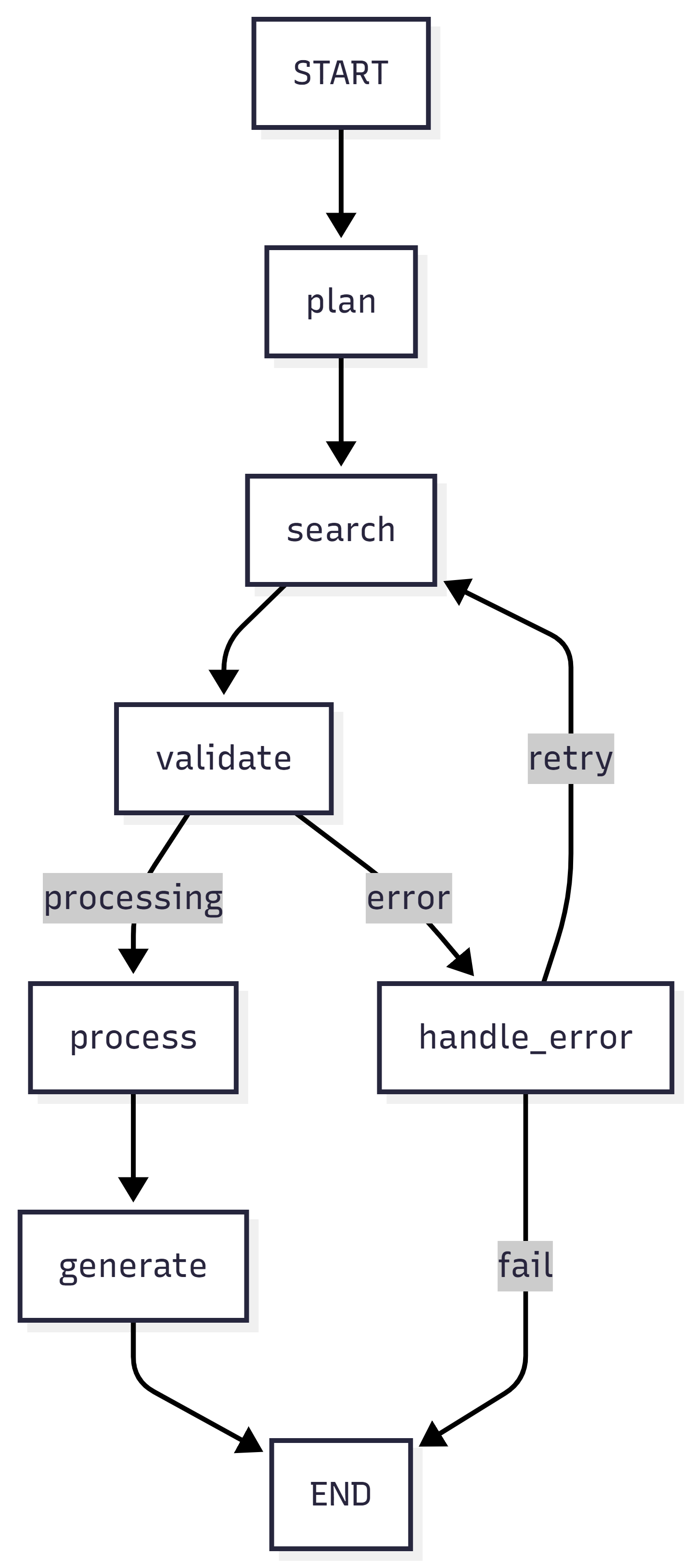

The Workflow

Each arrow is a decision. Each box saves state. If it fails on step 4, it resumes from step 4—not step 1.

Understanding the flow:

The happy path is straight through: plan → search → validate → process → generate → end. But production systems need error paths. The dotted lines show retry loops—if search fails, we can retry. If validation fails (insufficient results), we retry search. If we exceed max retries, we route to error handler which decides whether to retry or give up.

Checkpointing happens at every arrow. After planning completes, state is saved. After search completes, state is saved again. If execution crashes during processing, you resume from the last checkpoint—with your search results intact, no need to search again.

This is deterministic flow: explicit state, explicit routing, explicit error handling. No “hope the LLM figures it out” magic. You define exactly what happens in each scenario.

Step 1: Define State

State is the single source of truth. Every piece of information the agent needs to make decisions goes here. Let’s break down each field and why it exists.

from typing import TypedDict, Annotated, Literal

from langchain_core.messages import BaseMessage

from langgraph.graph import add_messages

class ResearchAgentState(TypedDict):

"""State for our research agent."""

# Conversation

messages: Annotated[list[BaseMessage], add_messages]

# Task

research_query: str

research_plan: str

# Search

search_queries: list[str]

search_results: list[dict]

# Processing

key_findings: list[str]

report: str # Control flow

current_stage: Literal[

"planning",

"searching",

"validating",

"processing",

"generating",

"complete",

"error"

]

retry_count: int

max_retries: int

error_message: str | NoneField-by-field breakdown: